Igbo language

| Igbo | ||

|---|---|---|

| Asụsụ Igbo | ||

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | West and West Central Africa | |

| Total speakers | 25 million (2006 Nigerian census) | |

| Language family | Niger-Congo

|

|

| Writing system | Latin alphabet, Nsibidi ideograms | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | Nigeria | |

| Regulated by | SPILC | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | ig | |

| ISO 639-2 | ibo | |

| ISO 639-3 | ibo | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

The Igbo language (Igbo: Asụsụ Igbo) is a tonal language spoken by over 25 million people who are primarily of Igbo descent. In southeastern Nigeria and parts of the Niger Delta, Igbo is spoken natively. The language was used by John Goldsmith as an example to justify deviating from the classical linear model of phonology as laid out in The Sound Pattern of English. It is written in the Latin alphabet, as introduced by British colonialists. Other scripts include the Ekpe (and related secret societies') Nsibidi ideograms.[1]

Igbo dialect continuum, distinguished by accent and orthography but almost universally mutually intelligible, including the Idemili dialect of Chinua Achebe's novel, Things Fall Apart; others are Umuahia, Onitsha, Enuani (Anioma), Ngwa, Awka (Oka), Mbaise, Nsukka, Orlu, Afikpo, Nsa, Oguta,Ikwerre, Etche, Egbema, Owerri, Bonny-Opobo, Ohuhu, Unwana.[2] There is apparently a degree of dialect leveling occurring. A standard literary language was developed in 1972; this is based on Owerri and Umuahia, though it omits the nasalization and aspiration of those varieties. There are related Igboid languages as well that are sometimes considered dialects of Igbo, the most divergent being Ekpeye. Some of these, such as Ika, have separate standard forms.

Contents |

History

The Igbo people first used Nsibidi ideograms developed by the neighboring Ekoi people for writing.[3] These ideograms existed among the Igbo and other related groups before the 1500s, but died out after it became popular amongst secret societies such as the Ekpe, who then made Nsibidi a secret form of communication.[4]

The first books to publish any Igbo words was Geschichte der Mission der Evangelischen Bruder auf den Carabischen (German: History of the Evangelistic Mission of the Brothers in the Caribbean), published in 1777.[5] Shortly after wards in 1789, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano was published in London, England, written by Olaudah Equiano, a former slave, featuring 79 Igbo words.[5] The narrative also illustrated various aspects of Igbo life based in detail, based on Olaudah Equiano's experiences in his hometown of Essaka.[6] Things Fall Apart- Chinua Achebe Things Fall Apart which concerns influences of British colonialism and Christian missionaries on a traditional Igbo community during an unspecified time in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, was published in 1959 written by Chinua Achebe. The bulk of the novel takes place in Umuofia, one of nine villages on the lower Niger. It possibly is the most popular and renowned novel that deals with the Igbo and their traditional life.[7]

Central Igbo, the dialect form gaining widest acceptance, is based on the dialects of two members of the Ezinihitte group of Igbo in Central Owerri Province between the towns of Owerri and Umuahia, Eastern Nigeria. From its proposal as a literary form in 1939 by Dr. Ida C. Ward, it was gradually accepted by missionaries, writers, and publishers across the region. In 1972, the Society for Promoting Igbo Language and Culture (SPILC), a nationalist organisation which saw Central Igbo as an imperialist exercise, set up a Standardisation Committee to extend Central Igbo to be a more inclusive language. Standard Igbo aims to cross-pollinate Central Igbo with words from Igbo dialects from outside the "Central" areas, and with the adoption of loan words.[8]

The wide variety of spoken dialects has made agreeing a standardised orthography and dialect of the Igbo language very difficult. The current Onwu orthography, a compromise between the older Lepsius orthography and a newer orthography advocated by the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures (IIALC), was agreed in 1962.

Vocabulary

Igbo, like many other West African languages, has borrowed words from European languages, mainly English. Example loanwords include the Igbo word for blue [blu] and operator [opareto].

Many names in Igbo are actually fusions of older original words and phrases. For example, one Igbo word for vegetable leaves is akwükwö nri, which literally means "leaves for eating" or "vegetables". Green leaves are called akwükwö ndu, because ndu means "life". Another example is train (ugbo igwe), which comes from the words ugbo (vehicle, craft) and igwe (iron, metal); thus a locomotive train is vehicle via iron (rails); a car, ugbo ala; vehicle via land and an aeroplane ugbo elu; vehicle via air. Words may also take on multiple meanings. Take for example the word akwükwö. Akwükwö originally means "leaf" (as on a tree), but during and after the colonization period, akwükwö also came to be linked to "paper," "book," "school," and "education", to become respectively akwükwö édémédé, akwükwö ogugu, ulo akwükwö, mmuta akwükwö. This is because printed paper can be first linked to an organic leaf, and then the paper to a book, the book to a school, and so on. Combined with other words, akwükwö can take on many forms; for example, akwükwö ego means "printed money" or "bank notes," and akwükwö ejị éjé ijẹ means "passport."

Proverbs

Proverbs and idiomatic expressions are highly valued by the Igbo people and proficiency in the language means knowing how to intersperse speech with a good dose of proverbs. Chinua Achebe (in Things Fall Apart) describes proverbs as "the palm oil with which words are eaten". Proverbs are widely used in the traditional society to describe, in very few words, what could have otherwise required a thousand words. Proverbs may also become euphemistic means of making certain expressions in the Igbo society, thus the igbo have come to typically rely on this as avenues of certain expressions.

Sounds

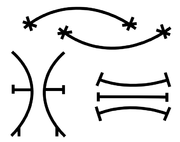

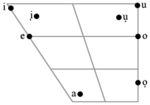

Igbo is a tonal language with two distinctive tones; high and low. In some cases a third, downstepped high tone is also recognized. The language features vowel harmony with two sets of vowels distinguished by pharyngeal cavity size and can also be described in terms of "advanced tongue root" (ATR).

In some dialects, such as Enu-Onitsha Igbo, the doubly articulated /ɡ͡b/ and /k͡p/ are realized as a voiced/devoiced bilabial implosive. The approximant /ɹ/ is realized as an alveolar tap [ɾ] between vowels as in árá. The Enu-Onitsha Igbo dialect is very much similar to Enuani spoken among the Igbo-Anioma people in Delta State.

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Labial- velar |

Glottal | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labio. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ŋʷ | ||||||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | kʷ | ɡʷ | k͡p | ɡ͡b | |||||||||

| Affricate | tʃ | dʒ | |||||||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | s | z | ʃ | ɣ | ɦ | |||||||||||||

| Approximant | central | ɹ | j | w | |||||||||||||||

| lateral | l | ||||||||||||||||||

Syllables are of the form (C)V (optional consonant, vowel) or N (a syllabic nasal). CV is the most common syllable type. Every syllable bears a tone. Consonant clusters do not occur. The semivowels j and w can occur between consonant and vowel in some syllables. The semi-vowel in CjV is analyzed as an underlying vowel 'ị', so that -bịa is the phonemic form of bjá 'come'. On the other hand, 'w' in CwV is analysed as an instance of labialization; so the phonemic form of the verb -gwá 'tell' is /-ɡʷá/.

Writing system

The most commonly-used orthography for Igbo is currently the Onwu (/oŋwu/) Alphabet. It is presented in the following table, with the International Phonetic Alphabet equivalents for the characters:[9]

| Letter | A | B | Ch | D | E | F | G | Gb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation (IPA) | /a/ | /b/ | /tʃ/ | /d/ | /e/ | /f/ | /ɡ/ | /ɓ~ɡ͡ɓ/ |

| Letter | Gh | Gw | H | I | Ị | J | K | Kp |

| Pronunciation | /ɣ/ | /ɡʷ/ | /ɦ/ | /i/ | /ɪ/ | /dʒ/ | /k/ | /ƥ~k͡p/ |

| Letter | Kw | L | M | N | Nw | Ny | Ñ | O |

| Pronunciation | /kʷ/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ŋʷ/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /o/ |

| Letter | Ọ | P | R | S | Sh | T | U | Ụ |

| Pronunciation | /ɔ/ | /p/ | /ɹ/ | /s/ | /ʃ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /ʊ/ |

| Letter | V | W | Y | Z | ||||

| Pronunciation | /v/ | /w/ | /j/ | /z/ | ||||

The graphemes <gb> and <kp> are described both as implosives and as coarticulated /ɡ/+/b/ and /k/+/p/, thus both values are included in the table.

<m> and <n> each represent two phonemes: a nasal consonant and a syllabic nasal.

Tones are sometimes indicated in writing, and sometimes not. When tone is indicated, low tones are shown with a grave accent over the vowel, for example <a> → <à>, and high tones with an acute accent over the vowel, for example <a> → <á>.

Usage in the Diaspora

With the devastating effects of the atlantic slave trade, the Igbo language was consequently spread by enslaved Igbo individuals throughout slave colonies in the Americas. These colonies include the United States, Jamaica, Belize, Barbados and The Bahamas among many other colonies. Examples can be found in Jamaican Patois: the pronoun /unu/, used for 'you (plural)', is taken from the Igbo language, Red eboe describes a fair skinned black person because of the reported account of a fair or yellowish skin tone among the Igbo.[10] Soso meaning only comes from the Igbo language.[11]

The word Bim, a name for Barbados, was commonly used by enslaved Barbadians (Bajans). This word is said to derive from the Igbo language, derived from bi mu (or either bem, Ndi bem, Nwanyi ibem or Nwoke ibem) (English: My people),[12][13] but it may have other origins (see: Barbados etymology).

See also

- Igbo people

- Igbo mythology

- Igbo music

- Delta Ibo

- Ukwuani

External links

- Ethnologue report on the Igbo language

- A History of the Igbo Language

- An insight guide to Igboland’s Culture and Language

- Journal of West African Languages: Igboid

Notes

- Awde, Nicholas and Onyekachi Wambu (1999) Igbo: Igbo-English/English-Igbo Dictionary and Phrasebook New York: Hippocrene Books.

- Emenanjo, 'Nolue (1976) Elements of Modern Igbo Grammar. Ibadan: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-154-078-8

- Surviving the iron curtain: A microscopic view of what life was like, inside a war-torn region by Chief Uche Jim Ojiaku, ISBN 1-4241-7070-2; ISBN 978-1-4241-7070-8 (2007)

- International Phonetic Association (1999) Handbook of the International Phonetic Association ISBN 0-521-63751-1

- The Bloc Party song Biko, uses the Igbo word of 'Dear' (Biko), which is the singer, Kele Okereke's parent's native language.

References

- ↑ "Nsibidi". National Museum of African Art. Smithsonian Institution. http://www.nmafa.si.edu/exhibits/inscribing/nsibidi.html. "Nsibidi is an ancient system of graphic communication indigenous to the Ejagham peoples of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon in the Cross River region. It is also used by neighboring Ibibio, Efik and Igbo peoples."

- ↑ "Igbo / A language of Nigeria". SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=ibo. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ↑ "Nsibidi". National Museum of African Art. Smithsonian Institution. http://www.nmafa.si.edu/exhibits/inscribing/nsibidi.html. "Nsibidi is an ancient system of graphic communication indigenous to the Ejagham peoples of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon in the Cross River region. It is also used by neighboring Ibibio, Efik and Igbo peoples."

- ↑ Oraka, L. N. (1983). The foundations of Igbo studies. University Publishing Co.. pp. 17, 13. ISBN 9-781-60264-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Oraka, L. N. (1983). The foundations of Igbo studies. University Publishing Co.. p. 21. ISBN 9-781-60264-3.

- ↑ Equiano, Olaudah (1789). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. p. 9. ISBN 1425045243. http://books.google.com/books?id=FXVkAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA9.

- ↑ Achebe, Chinua (1994.). Things fall apart. Anchor. p. 11. ISBN 0-385-47454-7.

- ↑ Oraka, L. N. (1983). The foundations of Igbo studies. University Publishing Co.. p. 35. ISBN 9-781-60264-3.

- ↑ http://www.omniglot.com/writing/igbo.htm

- ↑ Cassidy, Frederic Gomes; Robert Brock Le Page (2002). A Dictionary of Jamaican English (2nd ed.). University of the West Indies Press. p. 168. ISBN 9-766-40127-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=_lmFzFgsTZYC&pg=PA168. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ McWhorter, John H. (2000). The Missing Spanish Creoles: Recovering the Birth of Plantation Contact Languages. University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-520-21999-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=czFufZI4Zx4C&pg=PA77. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ↑ Allsopp, Richard; Jeannette Allsopp (2003). Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. University of the West Indies Press. p. 101. ISBN 9-766-40145-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=PmvSk13sIc0C&pg=PA101. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Carrington, Sean (2007). A~Z of Barbados Heritage. Macmillan Caribbean Publishers Limited. pp. 25. ISBN 0-333-92068-6.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||